The Air Force physical training (PT) construct does not effectively serve Airmen, the Air Force, or society as a whole.1 This ineffectiveness results in high injury rates and post-service disability costs and worsening mental health for Airmen. The proposed PT paradigm aims to create a healthier, more resilient, and more readily deployable force via a long-term approach to Airmen’s physical development, based on the concept of physical literacy.

The Problem

The Air Force does not have a physical fitness program; it has a reactive testing program—one that engages Airmen only if they fail to meet standards on the Physical Fitness Assessment (PFA), which determines overall physical health by evaluating cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, and core endurance.2 The program reflects a lack of intentional physical development combined with a superficial effort to promote physically fit Airmen. To make matters worse, the current PFA emphasizes physical attributes that only minimally prevent overtraining and acute injuries. The trifecta of less physically conscious recruits entering active-duty service, the increasing prevalence of overweight and obese members, and a lack of guidance on how to attain physical consciousness further leads to a large percentage of active-duty Airmen who are non-deployable. How can the Air Force aggressively achieve success given these factors?

As the author has witnessed in more than 15 years of working in the field with mostly enlisted personnel, the consequences of a reactive PT paradigm can be seen first at the individual level. These include eating disorders, dehydration for weight loss, increased anxiety, and overuse injuries from the “hurry up and train” mindset which is prevalent in preparation for PT tests. Air Force readiness rates reveal the second-order effects of less-healthy Airmen. Data collected in 2023 by the Operational Support Team at Dover Air Force Base (AFB), Delaware, showed that at one point during the calendar year, 387 Airmen were on profile for musculoskeletal injuries (MSKIs)—which involve bones, joints, tendons, muscles, or ligaments. With just over 3,800 active-duty military at Dover AFB, this represents a little over 10 percent of the local force.3 This means more than 10 percent of these military members could not take one or more PFA components.

These members either cannot deploy or are at a much greater risk of subsequent injury should waivers be granted allowing deployment. This base-level observation is corroborated by 2022 data from the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), which identifies MSKIs as the “primary cause of disability among military service members; accounting for 65% of medically non-deployable soldiers, and 70% of medical disability discharges.” These injuries affect more than 900,000 service members per year and are six times more common than battle injuries in deployment settings, making them responsible for the majority of medical evacuations.4

This data suggests that physical injury is the primary reason for Airmen not being ready to fight. And if they get to the fight, it is the main reason Airmen are forced to leave. Moreover, physical injury is the number one reason why Airmen are forced to leave the armed services for a non-conducive-to-service medical condition. Too many Air Force personnel are not physically prepared to do their job.

Additionally, national health trends are reflected in the military. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates a continuous, troubling trend of obesity and inactivity starting at younger and younger ages that impacts the Air Force.5 According to the ARFL’s STRONG (Signature Tracking for Optimized Nutrition and Training) Lab, an exercise science facility located at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, “Obesity impacts ~40% of US adults, with the military population not faring much differently—evidenced by active duty personnel gradually gaining excess body fat and becoming increasingly de-conditioned.” In terms of body composition, such trends are “worrisome, exacerbated at an alarming rate in recent years, and directly impacts the health, readiness, and retention of US service members.”6

The Air Force must modernize its approach to fitness, or it will continue to suffer in the long term, in the form of high injury rates and post-service disability costs as well as worsening mental health among Airmen. Current data demonstrates that physical activity is a cornerstone to mental health.7 Certainly worth noting is that veteran suicide rates also continue to outpace non-veteran suicides by 57 percent, surging to 166 percent for female veterans.8

Existing Guidance on Physical Fitness

Antiquated Air Force instructions (AFI), manuals, and facility guides compound the readiness issue. Existing guidance stifles innovation and critical thinking, and limits efficiency—evident as indoor and outdoor facilities fail to meet Airmen’s needs. Additionally, there is no assurance that procurement of AFI-mandated fitness equipment is data-driven, standard at every base gym, resulting in an abundance of archaic, single-exercise machines that are costly both in terms of expense and valuable facility floor space. For these reasons, many Airmen likely seek out off-base gyms and memberships.

A short review of applicable Air Force guidance yields little in terms of the definitions, significance, and methods of physical fitness. For example, AFI 90-506, Comprehensive Airman Fitness (CAF), describes physical fitness as “the ability to adopt and sustain healthy behaviors needed to enhance health and well-being.”9 Although the instruction states that physical fitness is comprised of four tenets—endurance, recovery, nutrition, and strength—little elaboration or explanation follows. Additionally, Department of the Air Force Manual (DAFMAN) 36-2905, DAF Physical Fitness Program, and DAF Instruction (DAFI) 34-114, Fitness, Sports, and World Class Athlete Program, offer no details on exactly how to train and equip Airmen for fitness.10 Instead, DAFMAN 36-2905 simply states that the fitness program should “motivate all members to participate in a year-round physical conditioning program that emphasizes total fitness, to include proper cardiorespiratory conditioning, muscular endurance training, and healthy eating,” advising that “commanders at all levels must incorporate physical fitness into their culture and establish an environment for members to maintain physical fitness, health, and performance to meet expeditionary mission requirements.”11

This guidance is vague and uncompelling, leading to fitness standards and follow-through that are generally inconsistent and ineffective. “Maintaining physical fitness, health, and performance” is often left to the individual, and Airmen are just as susceptible as other members of society to a backward slide into physical unfitness. Incorporating physical fitness into the “culture” likely varies across the board; for example, it may manifest as the commander encouraging their unit members to take an hour in the duty day for fitness, once or twice a week, or may involve nothing at all. A shift within the service is needed and requires multiple, concentrated lines of effort. The Long-Term Athlete Development (LTAD) model and its application, physical literacy, can launch this change.

Long-Term Athlete Development Model

The LTAD model “aims to improve health, physical activity and performance of all youth.”12 It is based on the principle that “it is imperative from a public health perspective that a structured, progressive, and integrated approach to . . . training is viewed as a developmental pathway for athletes of all ages and abilities.”13 This young athlete development concept employed by European national and club teams is gaining traction worldwide, seeing every youth participant as an asset to invest in over the long-term as if they were the next Lionel Messi or Serena Williams.

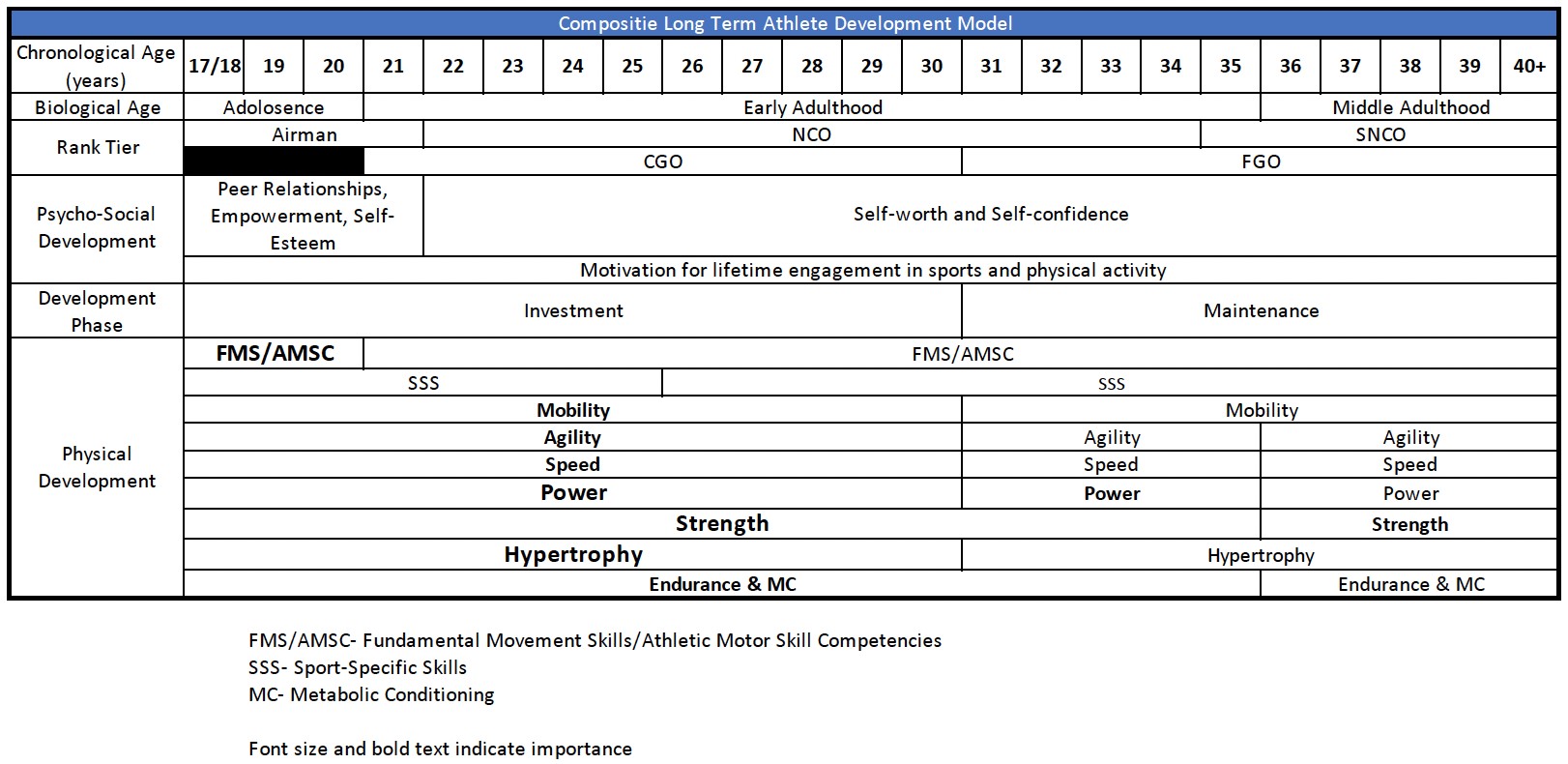

In Air Force terms, this would mean recognizing every lieutenant as a future colonel or every enlisted member as a future chief master sergeant. Accompanied by targeted physical competencies, LTAD provides a model that can be easily tailored to Airmen/athletes, meeting them where they are in their training age—or the length of time they have implemented regular, supervised resistance training—and customizing training accordingly so they can exceed those standards (fig. 1).14

Figure 1. Composite Long Term Athlete Development Model adapted to Air Force physical literacy15

By definition, physical literacy is “the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life.” It encompasses “physical capacities embedded in perception, experience, memory, anticipation, and decision-making.”16 In service terms, physical literacy is embodied in an empowered, confident Airman/athlete and competitor, who frequently and purposefully seeks and meets physical challenges and understands their short- and long-term benefits. Although the Air Force operates as if Airmen possess physical literacy, the STRONG Lab data indicates otherwise.17 Acknowledging clear deficiencies in service-wide physical fitness and intentionally developing physical literacy will help to improve service readiness and ultimately benefit Airmen’s overall quality of life.

Physical Literacy and LTAD Basic Training and Early Career

In alignment with the LTAD model, foundational physical literacy improvement must be an expected outcome of basic military training (BMT). It is during this initial exposure to the military lifestyle that the seeds of physical culture are planted. Instructors would conduct movement evaluations—such as observing running mechanics and performing squat analyses and posture critiques—and triage movement and mobility deficits. Athletes would then be placed into training groups that appropriately challenge and develop them depending on their level of physical literacy. This differs significantly from current Air Force physical training where virtually every recruit’s training is standardized.

During these daily, structured training sessions, Airmen would be coached on proper movement patterns and performance experts would directly address their movement deficiencies. Here, movement proficiency is as important as physical exertion. Instructors and trainers would establish physical literacy baselines, delivering more actionable insight than what the current PFA offers. This information could be stored in myFitness—the service’s fitness assessment management and maintenance system—and accompany Airmen to technical school, where they would continue their physical development along the LTAD model, and then through their respective first duty assignments and into their time in service. Additionally, training and workout apps can track individual workouts prescribed by LTAD-associated staff, bridging the gap between the Air Force portal (AFNET) availability and individual commercial devices and providing continuity for Airmen and their strength and conditioning coaches.

Achieving Physical Literacy

The current PFA emphasizes cardiovascular health with the cardiorespiratory component score contributing to 60 percent of the overall score. According to STRONG Lab, “Cardiorespiratory fitness is necessary to war-fighter readiness” and “aerobic capacity is held in high accord for good reason”—it also marks a decrease in heart disease risk.18 While this component provides valuable insight into systemic wellness, however, it fails to address the musculoskeletal injury rates that affect readiness, early redeployment, and medical discharge. Troops are not leaving the battlefield or the service due to complications from cardiopulmonary disease; rather, they are being sent home and/or removed from service because they do not know how to safely generate and/or absorb physical forces.19 The PFA needs to be modernized to address this issue to assess relative strength and power in addition to heart health.

In 2017 the American College of Sports Medicine found that resistance training is key to injury prevention, and its benefits are seen across all levels of physical literacy—from non-competitive beginners to professional athletes.20 Several studies have corroborated this correlation between resistance training and injury prevention.21 In 2021, for example, one researcher found strength training reduced sports injuries by up to a third and overuse injuries by up to a half.22 Current Air Force assessments may thus be undervaluing muscular strength and endurance as an indicator of health and readiness.

The Marine Corps and Army have already transitioned toward a more functional fitness assessment that better addresses skills and competencies used on the battlefield.23 The Air Force Academy’s Physical Fitness Test (PFT) is a start in the right direction; it includes pull-ups, a broad jump, sit-ups, push-ups, and a 600-yard run. Replacing the sit-ups with a relative strength-oriented trap bar deadlift evaluation would result in a fitness test that addresses nearly all an Airmen’s needs: aerobic capacity, strength, power, agility, and anaerobic power. The repetition standards would need to be evaluated to find meaningful cut scores across active-duty age ranges.

The next line of effort in this physical fitness culture change is the dedication of time and resources. Physical literacy is about establishing the habit of moving well. Commanders at all levels must understand the value that physical literacy brings to their Airmen and demand that Airmen take advantage of it. This shift in mindset would need to be taught and exemplified at all levels of professional military education (PME), including enlisted PME and unit commander prep courses.

Advancing on the Objective

Addressing the dedication of resources to improve Airmen’s physical literacy is a more complex task, yet one that remains significant to maximize success.

Outmoded Facilities

Base fitness centers are modeled after recreation-style gyms like the YMCA rather than performance-centered facilities that cater to athletes and athletic development. These models clash with strength and conditioning industry recommendations and the LTAD model needed in the Air Force. The new PT paradigm requires a move toward open floor spaces, power racks, and free weights utilized in athletic development. Yet there are three prominent barriers to implementation: AFI mandates, misguided demographic targets, and lack of staff trained in human performance.

Official guidance, including DAFI 34-114 and Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC): Fitness Centers, must be updated to reflect advances in the human performance industry and to upgrade the facility landscape at bases.24 Currently, there are Air Force facilities that meet LTAD goals, including the Air Force Academy’s Falcon Athletic Center Weight Room, and the 10th Special Forces Group training facility.25 Such Air Force fitness centers designed and equipped to elicit physical literacy outcomes for 18- to 40-year-olds have specific layouts and multi-capable equipment, can adequately support peak utilization hours, and are staffed to provide coaching and programming expertise. This design concept should be the template used for LTAD implementation from introduction and familiarization during BMT to utilization at all Air Force bases. Retrofitting existing fitness centers to conform to this template is less costly, more easily implemented in the short-term, and will see the quickest results. The Air Force is accustomed to replacing a large percentage of its fitness center equipment on an annual basis, so this transition should not be unfamiliar.

Secondly, the needs of non-target populations—including retirees, dependents, and civil service personnel who may opt for amenities like selectorized machines or aerobics rooms—tend to have considerable impact on facility design, thus challenging the move toward an LTAD design. Yet any negative effects of the LTAD model may have on such demographics, such as disruptions to familiar fitness routines, can be minimized with dedicated introductions to equipment and layouts and support by strength and conditioning professionals.

While fitness centers need directors and equipment managers, they also need staff educated in strength and conditioning. An experienced human physical performance specialist with Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) credentials—administered by the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA)—should be on staff at every Air Force fitness center. Ideally, this should be the fitness center director, designated as the human performance director (DHP), who should also have graduate-level education in a related field to match their on-the-ground coaching acumen. Ideally, all fitness center staff should have a CSCS or be working toward the credential just below this certification—the NSCA’s Tactical Strength and Conditioning Facilitator—while employed by the fitness center. This latter credential does not require a college degree like the CSCS, making it attainable for enlisted force support Airmen, who routinely rotate through the fitness center.

Physical Literacy Buy-In

The final challenge to overcome is helping Airmen see the importance of LTAD and physical literacy. The Air Force can meet this challenge through two means. First, a physical literacy score should be included in performance evaluation scoring. The Air Force must revise current assessments to evaluate fitness with more than a “Pass/Fail” standard, given the economic and social costs of a less-than-healthy Air Force—for example, $548 million in direct patient care costs and 2.4 million medical visits annually from MSKIs.26 Both the Marine Corps and Army, which incorporate physical performance in their evaluation scores, can provide insight on a number of potential solutions.27

Second, the value of physical literacy can be instilled by monetarily incentivizing physical performance. Passes for excellent scores can be inconsistently awarded at a commander’s discretion and may be culturally frowned upon when cashed in. A monthly stipend would standardize the award for above average or excellent scores in physical literacy. Theoretically, a high degree of physical literacy at the time of separation/ retirement likely means a lesser degree of preventable MSKI-related disability in the future. Thus, this monthly stipend should be considered as a preventative cost, ultimately benefiting the Air Force with lower long-term disability costs. Such an approach is proactive and long-term rather than reactive and short-term.

Conclusion

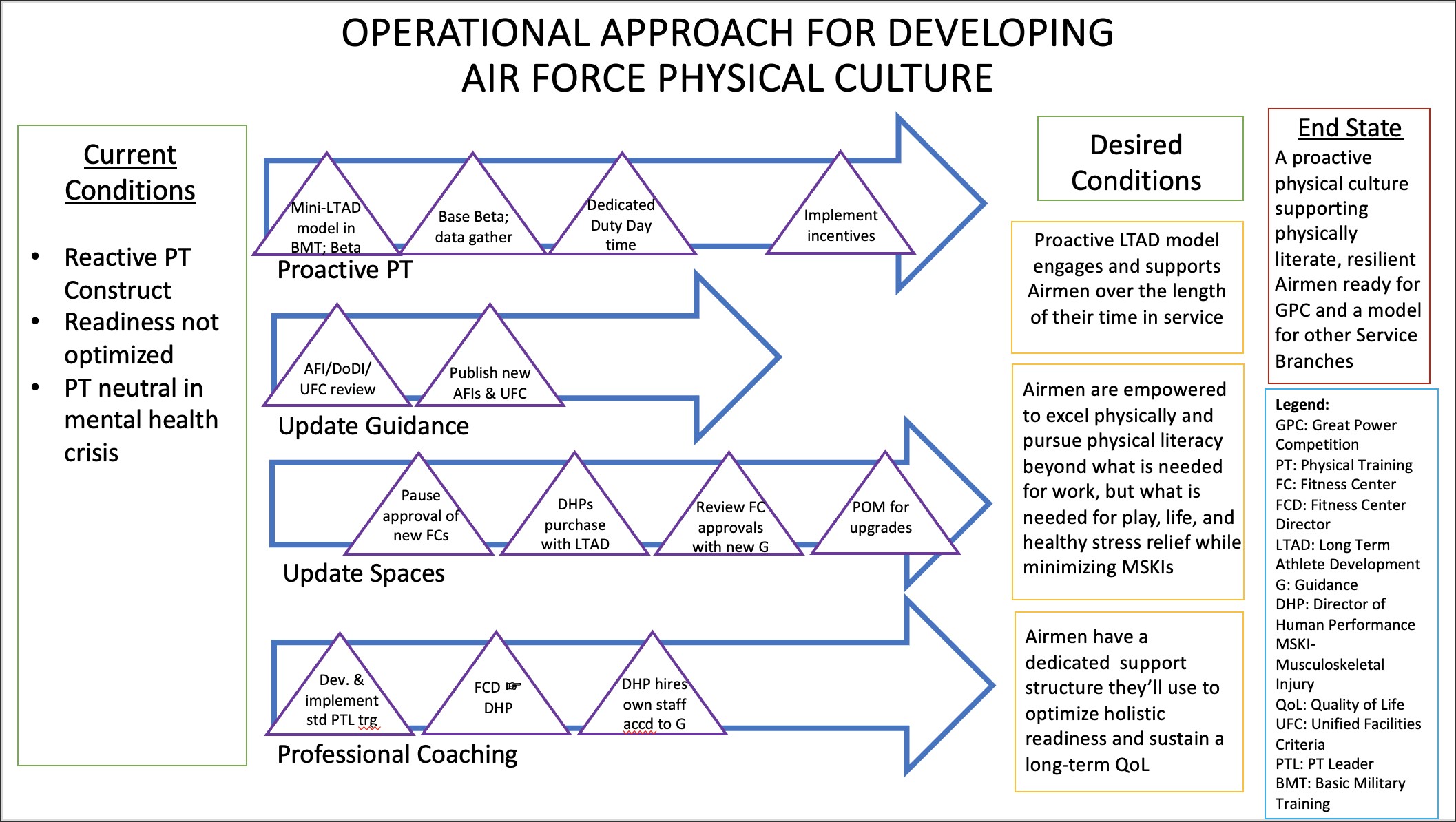

Implementing the LTAD model requires a multi-faceted approach. It takes deliberate introduction in BMT, follow-through with all Air Force bases, and commander buy-in at all levels. It also requires updating guidance, allocating resources to redesign fitness centers and employ and grow strength and conditioning professionals, and incentivizing physical literacy monetarily (fig. 2).

Figure 2. LTAD operational approach

A new approach is needed to supply combatant commanders with healthier and more resilient Airmen in order to deter a near-peer adversary across the Pacific, as well as emerging threats on the periphery. The Long-Term Athlete Development model, which drives a new paradigm of fitness and wellness, promotes physical literacy as an outcome. By investing in physical literacy, the Air Force also will see improved mental health outcomes. Furthermore, there is no better time, physiologically speaking, for Airmen to create these quality-of-life-improving adaptations than during the time they serve the Air Force. The Air Force needs to take advantage of this time by giving Airmen every tool available to optimize this change.

Major Anthony Hemphill, USAF, director of operations, 326th Training Squadron, is a certified strength and conditioning specialist. He holds a master of arts in education from the University of Colorado.

1 The author would like to thank the following individuals for their contributions to the article: James Bockas, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Briggs, Lieutenant Colonel Cody Butler, and Brett Campfield.

2 Department of the Air Force Manual (DAFMAN) 36-2905, DAF Physical Fitness Program (Arlington, VA: Secretary of the Air Force SecAF, April 21, 2022), https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/.

3 436 Medical Group, “Profile Data Scrub,” Excel spreadsheet, Dover AFB, DE, February 6, 2023.

4 Robert Briggs, “News Flash,” STRONG Connector, Air Force Research Laboratory, no. 3 (July 2022): 1.

5 C. D. Fryar, M. D. Carroll, and J. Afful, Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Severe Obesity among Children and Adolescents Aged 2–19 Years: United States, 1963–1965 through 2017–2018 (Washington, DC: National Centers for Health, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/.

6 Joshua Hagen and Nina Stute, “Fresh Findings,” STRONG Connector, no. 3 (July 2022): 2.

7 Paul Reed, “Physical Activity is Good for the Mind and Body,” health.gov, December 15, 2021, https://health.gov/; and see Nicholas Fabiano et al., “The Effect of Exercise on Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Journal of Effective Disorders 330 (2023), https://doi.org/; and Michael Grasdalsmoen et al., “Physical Exercise, Mental Health Problems, and Suicide Attempts in University Students,” BMC Psychiatry 20 (2020), https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/.

8 Ways Veterans Differ from the General Population (Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs VA, January 2022), https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/; and 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (Washington, DC: Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, VA, November 2023), https://department.va.gov/.

9 Air Force Instruction (AFI) 90-506, Comprehensive Airman Fitness (CAF) (Arlington, VA: SecAF, April 2, 2014).

10 DAFMAN 36-2905; and DAF Instruction (DAFI) 34-114, Fitness, Sports, and World Class Athlete Program (Arlington, VA: SecAF, December 15, 2022; Incorporating Change 1, April 9, 2024), https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/.

12 Kevin Till et al., “A Coaching Session Framework to Facilitate Long-Term Athletic Development,” Strength and Conditioning Journal 43, no. 3 (June 2021), https://doi.org/.

13 Rhodri S. Lloyd, et al., “Long-Term Athletic Development, Part 1: A Pathway for All Youth,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 29, no. 5 (May 2015), https://doi.org/.

14 Gregory G. Haff and Travis N. Triplett, eds., Essentials of Strength and Conditioning, 4th ed. (Champaign, IL: National Strength and Conditioning Association, Human Kinetics, 2016).

15 See Lloyd et al. "Long-Term Athletic Development."

16 Till et al., “Coaching.”

17 Hagen and Stute, “Findings.”

20 Jay Hoffman, Resistance Training and Injury Prevention (Indianapolis, IN: American College of Sports Medicine, 2017).

21 See Timothy J. Suchomel, Sophia Nimphius, and Michael H. Stone, “The Importance of Muscular Strength in Athletic Performance,” Sports Medicine 46, no. 10 (October 2016), https://doi.org/; Jeppe Bo Lauersen, Thor Einar Andersen, and Lars Bo Andersen, “Strength Training as Superior, Dose-Dependent and Safe Prevention of Acute and Overuse Sports Injuries: A Systematic Review, Qualitative Analysis and Meta-Analysis,” British Journal of Sports Medicine 52, no. 24 (December 2018), https://doi.org/; and “Strength Training as Superior, Dose-Dependent and Safe Prevention of Acute and Overuse Sports Injuries: A Systematic Review, Qualitative Analysis and Meta-Analysis,” British Journal of Sports Medicine 52, no. 24 (December 2018), https://doi.org/.

22 Jeppe Bo Lauersen, Ditte Marie Bertelsen, and Lars Bo Andersen, “The Effectiveness of Exercise Interventions to Prevent Sports Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials,” British Journal of Sports Medicine 48, no. 11 (June 2014), https://doi.org/.

24 DAFI 34-114; and United Facilities Criteria (UFC): Fitness Centers, UFC 4-740-02 (Washington, DC: DoD, February 3, 2019; Change 1, May 30, 2019).

26 Hagen and Stute, “Findings.”

27 “Get Fit, Stay Ready”; and “Physical Fitness.”