Masters of the Air, episode 7, “Part Seven,” directed by Dee Rees, written by John Orloff. Aired March 1, 2024, Apple TV+.

Episode 7 begins the final third of the story of the 100th Bombardment Group’s war, picking up after a significant chronological leap, from mid-October 1943 to March 1944. Many changes are underway both within the group and the wider war. Two narrative threads dominate this episode: the shifts in aerial strategy and tactics that would ultimately bring the Allies air mastery over Occupied Europe, and the story of Majors John “Bucky” Egan (Callum Turner) and Gale “Buck” Cleven (Austin Butler) from behind the barbed wire of Stalag Luft III.

Perceptions of the Allied prisoner of war (POW) experience are commonly shaped by Hollywood portrayals, ranging from the black comedy Stalag 17 (1953) to the star-studded, embellished classic The Great Escape (1963). This series opts for a more realistic, gritty portrayal. Although the Luftwaffe ran its camps broadly in line with the Geneva Convention, there is no trace of a Hogan’s Heroes’ (1965–71) sensibility here. Malnourished prisoners catch an unfortunate cat to augment their meager rations, and we see a POW shot and wounded by guards for a minor infraction. The captured airmen endure stultifying boredom, punctuated only by infrequent mail calls, endless card games, and occasional bits of war news gleaned from an illicit crystal radio set that Cleven manufactures from scrounged components. The POWs learn of the stalemate in the Italian theater as well as major Soviet victories on the Eastern Front—a nod to the Red Army’s contribution to victory in Europe.

Egan and Cleven naturally discuss the possibility of escape, but the prospects seem dim. The camp, located deep inside Germany near Sagan in Silesia (now Poland), is far from potential resistance contacts. They are bystanders to the “Great Escape,” the March 24, 1944, mass tunnel breakout of 76 Royal Air Force prisoners. The camp’s new acting commandant tells the senior US officers that 50 escapees were executed. He hints darkly that control of Allied POWs might soon pass from the military to the Gestapo and asks the lead POW to identify the Jewish officers in the camp. He replies that there are only Americans present. Ultimately, Egan and Cleven resign themselves to sitting out the war.

In reality, despite fears of reprisals, little happened to the POWs remaining at the camp. Appalled by the killings, the Luftwaffe staff provided materials for the construction of a memorial.1 Many accounts of the Great Escape use the term “executed” to describe the fate of the fifty, implying some sort of due process was involved; however, these men were murdered on orders from the highest level. Though the decisionmakers in question were beyond mortal judgment after 1945, the British painstakingly investigated and arrested the actual Gestapo killers. Most, after a fair trial, were executed.

Back at Thorpe Abbotts, the 100th endures the crescendo and eventual turning point of the daylight bomber offensive. As appropriate, most higher-level strategy debates and decisions are not dramatized as little of this percolated down to the crews flying the missions. After the crisis of autumn 1943, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, the Army Air Forces chief, cleaned house at the Eighth Air Force, sending its commander Major General Ira Eaker to the Mediterranean and replacing him with Major General James Doolittle, hero of the 1942 Tokyo raid. Lieutenant General Carl Spaatz took over a new headquarters, US Strategic Air Forces in Europe, with oversight of both the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces, the latter operating out of newly captured Italian bases. Arnold, in a New Year’s 1944 message to all commands, insisted that gaining air superiority was the priority: “Destroy the German Air Force wherever you find it—in the air, on the ground, and in the factories.”2 A dramatic series of February 1944 raids on German aircraft factories, dubbed “Big Week”—not portrayed in the series—began the progressive eradication of the German fighter force.3

The effect of these sweeping changes is slow to reach Thorpe Abbotts. The group was mauled in the first major Army Air Forces attack on Berlin on March 6, 1944. The losses—69 bombers, 15 from the 100th—were the highest of the entire war.4 The portrayal of the damaged planes’ return contains some of the series’ most powerful images. A crew hatch is flung open and dozens of empty .50-caliber brass casings spill out. A quick shot of a shattered, bloodstained ball turret evokes Randall Jarrell’s short poem “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.” Medics swarm over the shredded bombers, extricating and treating crewmen with all manner of horrible injuries. Some years ago, I interviewed a former Eighth Air Force medic, and he freely admitted that he still had nightmares about things he had seen 75 years earlier.

Yet amid the carnage of “Black Monday,” and another brutal raid on the Reich capital two days later, some rays of hope emerge. Two missing crewmen return to Thorpe Abbotts after months spent evading capture with the help of the resistance. In line with US policy they are taken off flying status; it was too risky to permit personnel who had contact with the resistance network to return to the air. Captain Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal’s (Nate Mann) crew hits the milestone of 25 missions and completes their tour, but their celebration is tempered by the announcement that an operational tour is now 30 missions. This “moving of the goal posts” seems capricious and heartless to the crews—but the rationale was based on a hard look at the actuarial tables. Experienced crews were a valuable commodity; with the Eighth Air Force expanding dramatically as 1944 began, Doolittle realized that he needed to hang onto his seasoned veterans. And, though it was hard to discern, airmen’s chances of survival were improving as spring 1944 wore on.

The episode also depicts the arrival of the North American P-51 Mustang escort fighter, which combined superior performance and long range. With drop tanks they could accompany the bombers to Berlin and back. Acting Group Commander Lieutenant Colonel John Bennett (Corin Silva) tells Rosenthal that, from here on in, the bombers will essentially function as “bait” to bring the German fighters into the sky so the escorts can destroy them. And indeed, the Luftwaffe day fighter force lost its entire frontline strength—and irreplaceable pilots—during spring 1944.

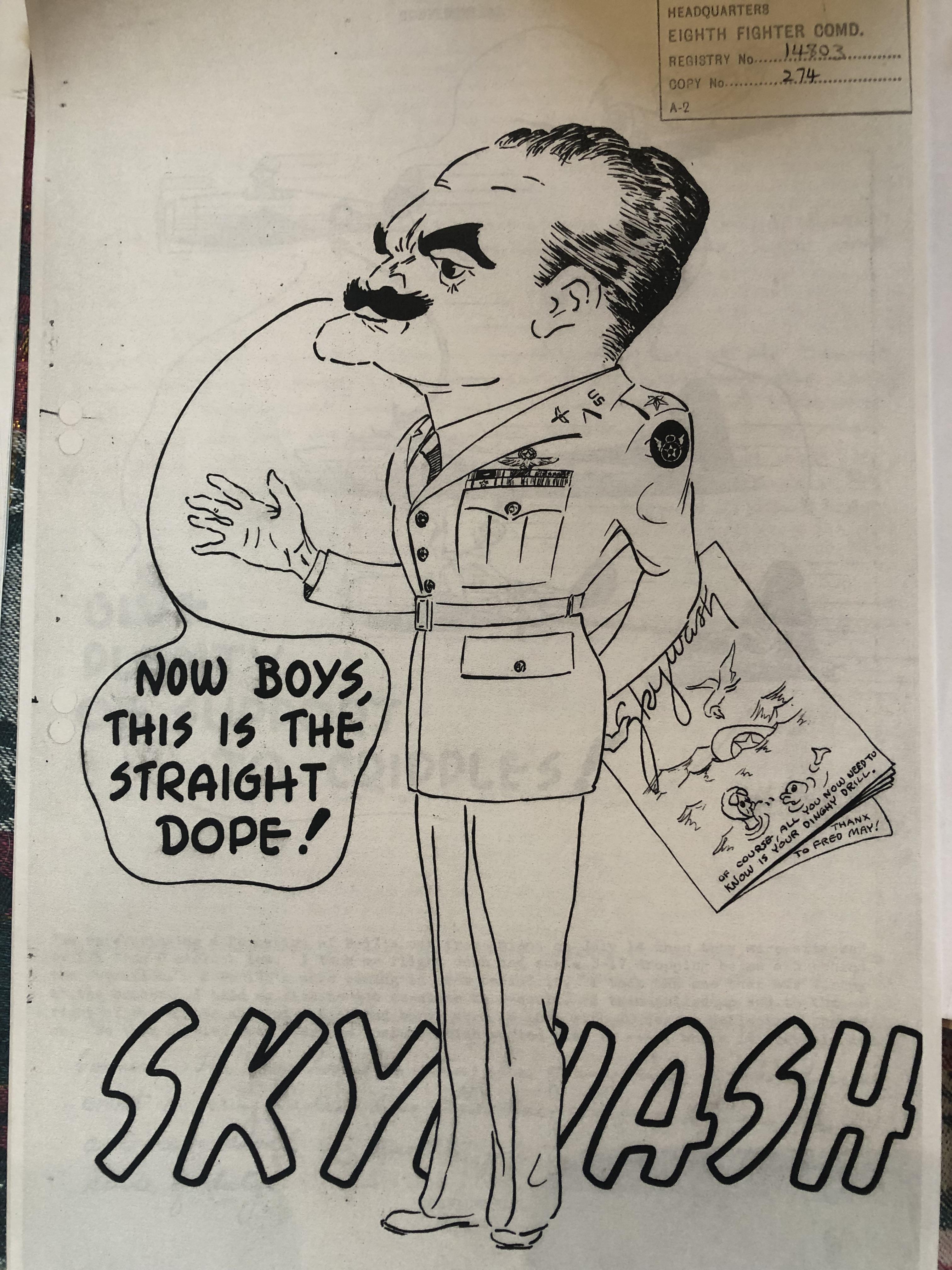

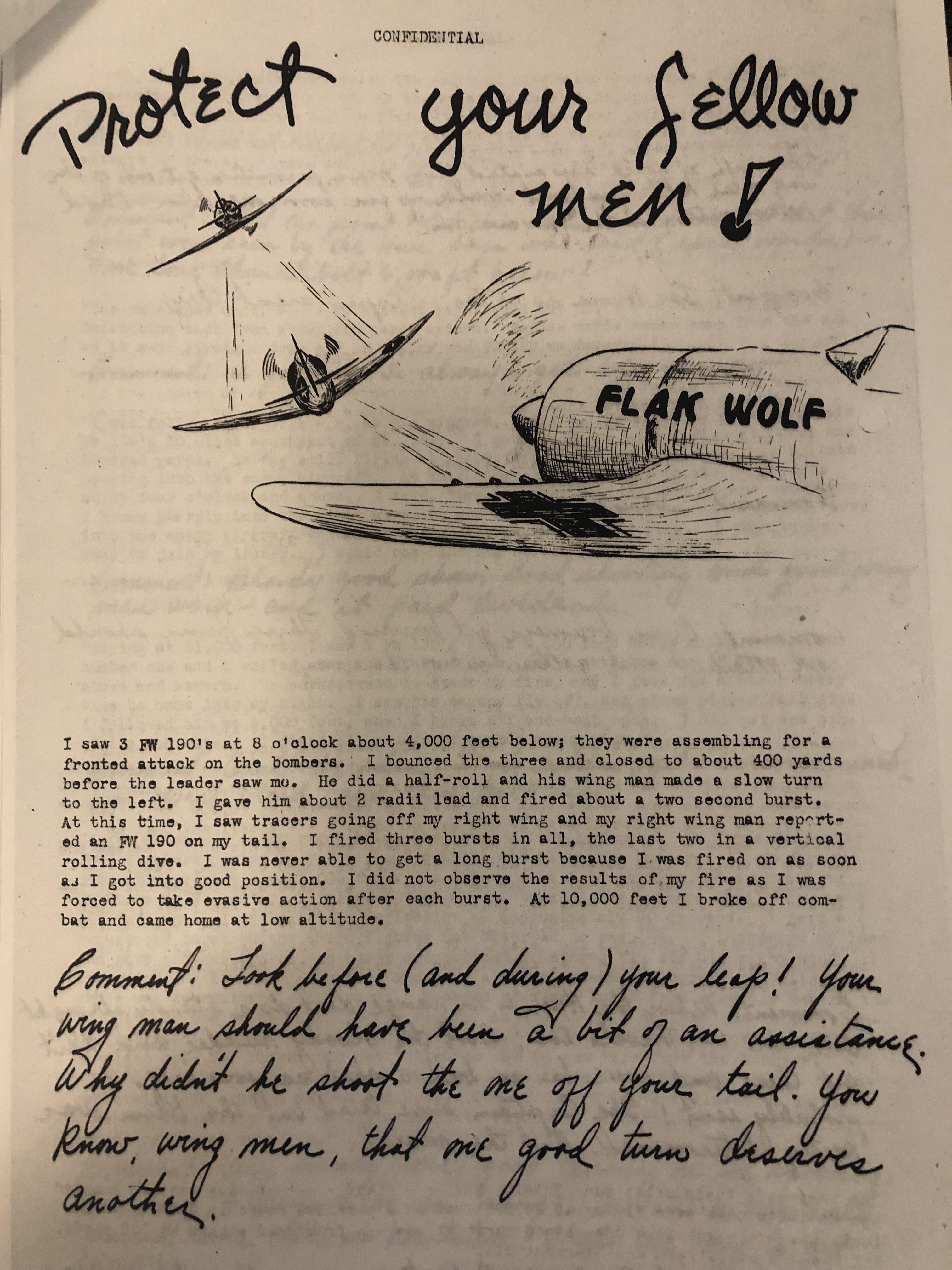

In the series, the arrival of the game-changing Mustangs is almost a deus ex machina. The reality is more complex—and more interesting. Masters of the Air focuses on the bomber experience, but it is worth emphasizing that VIII Fighter Command went through its own painful learning curve. Debates about close escort versus fighter sweeps, development of “relay” procedures to ensure coverage of bomber formations for as long as possible, and technical innovations such as auxiliary fuel tanks, were ongoing.5 The Mustang itself was a fortuitous combination of an American airframe and a British Merlin engine. The command even published a 1940s version of a “wiki” that made the rounds: Skywash—a collection of combat report extracts with commentary and “lessons learned” from combat leaders.6

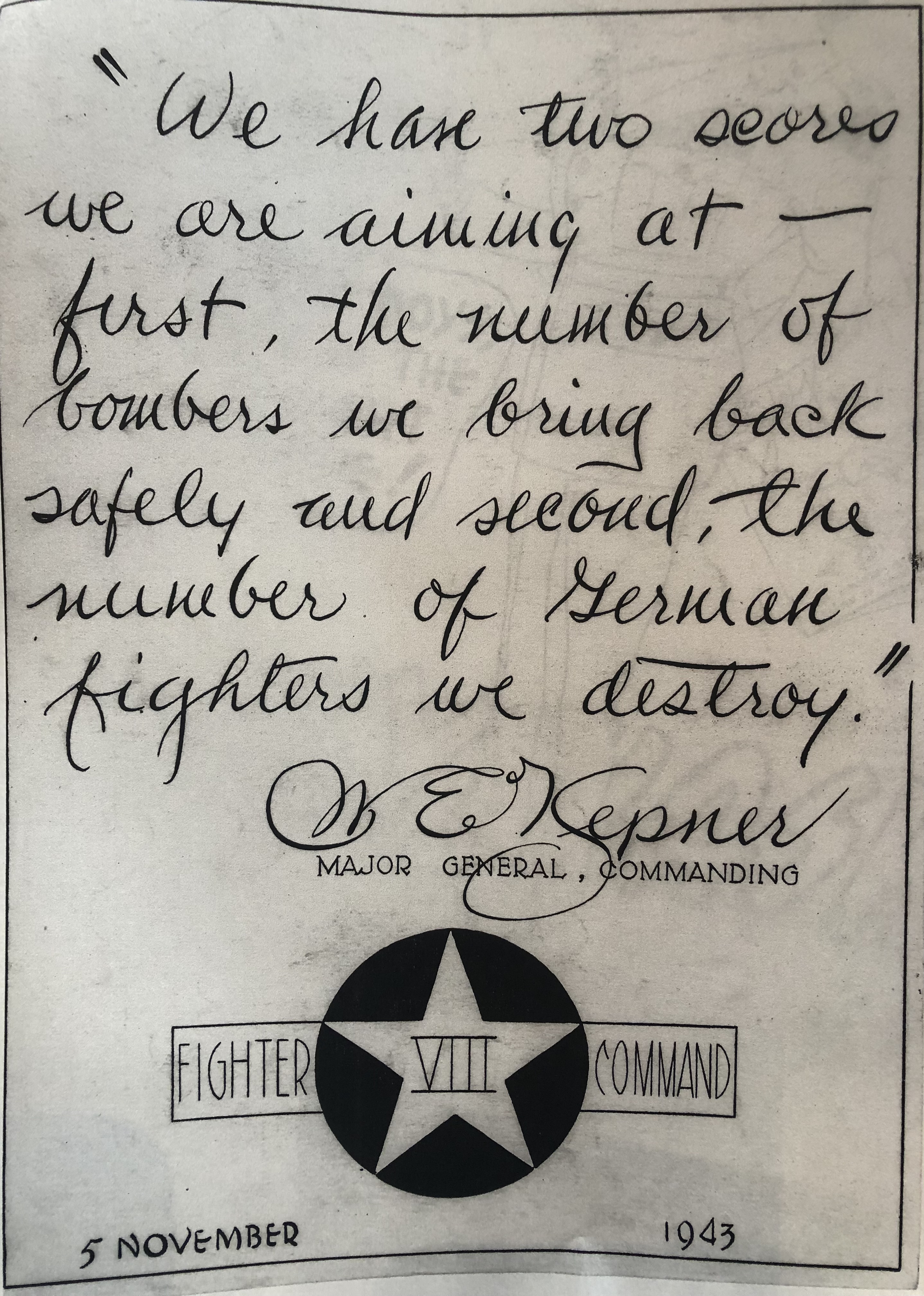

Figure 1: Illustration from the VIII Fighter Command tactical publication Skywash from November 1943 demonstrates the growing realization that destroying German fighters was as important as protecting the bombers.

Figure 2: Brigadier General Frank “Monk” Hunter, first commander of VIII Fighter Command, reminds his pilots that they can get “the straight dope” from Skywash.

Figure 3: Typical page from Skywash, An extract from a pilot’s combat report with handwritten commentary from a more experienced fighter leader, conveying a gentle reminder and lessons learned.

Though the episode implies that an early 1944 order from Doolittle caused the switch in focus from protecting bombers to destroying enemy fighters, the command had for months been moving toward such an air superiority strategy. A November 1943 general order stressed, “We have two scores we are aiming at; first the number of bombers we bring back safely, and second the number of German fighters we destroy.”7 Much of the heavy lifting of the early 1944 air superiority battles was borne by the P-47 Thunderbolt fighters, although the incomparable Mustang garners most of the good press.

The episode concludes with Rosenthal telling soon-to-be Group Commander Bennett that he is volunteering for a second tour. Rosenthal would ultimately command two of the 100th Bomb Group squadrons and stand in the front rank of the combat leaders who turned things around for the group. As group navigator Harry Crosby sums up in his memoir: “Bucky Egan and Buck Cleven gave the 100th its personality. Bob Rosenthal helped us want to win the war . . . everybody wanted to be like Rosie.”8

Richard R. Muller, PhD

1 Paul Brickhill, The Great Escape (New York: W. W. Norton, 1950), p. 191.

2 Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate, The Army Air Forces in World War II: Volume III, Europe: Argument to V-E Day (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951), 8.

3 Donald Caldwell and Richard Muller, The Luftwaffe over Germany: Defense of the Reich (London: Greenhill, 2007), 144–89.

4 Jeffrey Ethell and Alfred Price, Target Berlin: Mission 250—6 March 1944 (London: Jane’s, 1981), 142.

5 VIII Fighter Command, “Tactics and Techniques of Long Range Fighter Escort in VIII Fighter Command,” July 25, 1944, US Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA) 524.522.

6 VIII Fighter Command, Skywash, no. 1, May 1943, AFHRA 524.549A.

7 VIII Fighter Command, Skywash, no. 5, November 1943, AFHRA 524.549A.

8 Harry H. Crosby, A Wing and a Prayer (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), 320.